With latest defamation lawsuit, Texas abortion advocates are fighting for their rural clients

For months, anti-abortion extremists have targeted rural Texas towns and attacked reproductive rights and justice organizations in an effort to suppress residents’ rights to health care.

Now, they’re being taken to court. Again.

The Lilith Fund for Reproductive Equity, The Afiya Center, and Texas Equal Access (TEA) Fund, are firing back with a defamation lawsuit against the malicious actions of the extremists who labeled the organizations as “criminal” and banned them from working in the east Texas city of Waskom.

During their first lawsuit earlier this year, The Lilith Fund and TEA Fund worked with the ACLU and ACLU of Texas to file a lawsuit that (successfully) challenged not only the ordinance in Waskom, but other anti-abortion ordinances like it in Naples, Joaquin, Tenaha, Rusk, Gary and Wells. The lawsuit was dropped in May after cities involved agreed to remove all language associating the organizations as criminal.

But to protect the people they serve, all Texans, and the work they can continue to provide, the organizations involved want to make sure something like this never happens again.

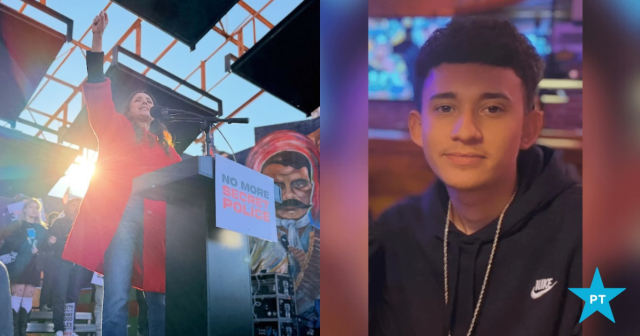

“I think it’s a historic thing that’s being done right now,” said Kamyon Conner, executive director of TEA Fund. “We’re filing this suit to reject the lies and damaging language spread by anti-abortion extremists, which they always do about our organizations, and to remind Texans that we’re here to help them get the essential abortion care that they need.”

TEA Fund also hopes to reduce the shame and stigma perpetuated among Texans seeking abortions as a result of the lies spread against their organizations, so people know abortion is still legal in Texas. Most of the towns targeted by these ordinances are areas TEA Fund serves in their work as an abortion fund serving the northern region of the state.

“The places that have been targeted by the folks we’re suing are small, rural areas for the most part, and there’s overall, in general, limited access to health care already,” said Conner. “The folks that are in these towns that might be seeking abortion — or any type of other health care — already disproportionately have barriers placed in front of them. It’s a direct attack on them as well, not just all of the people we serve, and not just the people that make up our volunteer base and staff, but as well as the people in the communities where these ordinances were put in place.”

The Lilith Fund, an abortion fund serving central and southern Texas, hopes the lawsuit will not only help Texans seeking abortions, but also prevent anti-abortion opponents from attempting something similar in the future.

“We want to send a message to Texans, but also to other local governments and advocates, that they cannot get away with calling us criminals, and they cannot decry that our work is harmful in any way,” said Amanda Williams, executive director of The Lilith Fund. “[Our work] is centered around compassion, love, and support for people seeking abortion care. This is really about fighting back against the hostility from these anti-choice extremists who have made it their mission to intimidate, spread lies, and intend to create harm against the people who are having abortions, and the people who are supporting others in their pursuit of exercising their bodily autonomy.”

Anti-choice extremists set a dangerous precedent by targeting reproductive health, rights, and justice advocates by name. While the organizations have seen harassment on social media before, to make it public record in local municipalities is “a bold, targeted attack.” It cannot be the new normal.

Marsha Jones, executive director of The Afiya Center, the only Black-led reproductive justice organization in North Texas, said their organization’s work is “varied” and they work with many different entities in the state of Texas, so they felt they had more to lose if they didn’t fight back.

“Our work is not just abortion or pro-choice work,” Jones said. “We are Black women, a Black-led organization, and we are very out with the work that we do. It could be literally dangerous for us being that that is who we are and we live in a state like Texas.

The Afiya Center, which provides practical support for Black women seeking abortions in Texas as part of their work, has received a steady number of calls for support since COVID-19 forced government shutdowns, something Jones attributes to factors that may be compounded by the pandemic for Black women.

“People are in a space where they’re not going to have the ability to negotiate how, and who, and when sex happens,” Jones said. “We knew that these would be women who would also be essential workers, who can’t afford it [or] don’t have health care, and would not be able to stop and start parenting or continuing a full term pregnancy at this point in their life.”

Having the word “criminal” attached to any organizations’ name would hurt their work.

“The work that we do with maternal mortality, the work that we do with Black women living with HIV, the work that we do with transgender women -- that work can be so impacted,” Jones continued. “So much of Afiya’s work is dependent on relationships with those funded by the state that there was, and is, a real concern that having ‘criminal’ associated with their organization could jeopardize those relationships entirely.”

While accurate reporting from states on maternal mortality in the U.S. falls short, The Afiya Center’s 2019 State of Black Women report outlines the way our current political climate “has created socioeconomic and health disparities that exist among Black women in Texas”, and it highlights that Texas has the highest maternal mortality rate not just in the U.S., but in any developed country in the world; Black women are 243% more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women in the U.S.

Most maternal-related deaths could have been prevented and are a direct result of discrimination and structural racism against Black women among our healthcare system, and The Afiya Center has shown the various ways they’re prepared to work with their elected officials to identify policies in need of reform, propose policy solutions rooted in human rights and hold government accountable to human rights standards.

“In rural areas, Black women are more likely to be poor and more likely to be dealing with stigma that’s attached to their reproductive choices, which means they’re going to have less access and not necessarily have the means to travel to get the services they need – and they’re not always going to be welcome,” Jones said, noting that racism, bias, and implicit bias is even more prevalent in rural areas as well. “That implicit bias is going to show it’s face all the time and it’s going to recreate barriers for folks receiving this care. It is so important that folk know there are folk who look like them and who represent them doing this work. It is important that people know, one, we’re here doing this work and we’re on the ground doing it for Black folk unapologetically, and two, we are doing this to serve those voices that so seldom are heard” she continues.

As one of the three BIPOC-led organizations involved in the lawsuit, Williams said there’s also a personal component to it.

“We can’t remove our identities as people of color, especially in reproductive justice work … [and] what we see on our hotline, which is primarily [contacted by] Black women and Latinx women, [is that] this attack absolutely has had implications on their well-being, on their ability to access healthcare, [and] any time that our work is jeopardized that means that access is going to continue to be disseminated in the state,” she said.

The work of these organizations is built around honoring the communities that we’re a part of, and the communities who are calling every day because they are shut out from access due to systemic oppression.

When anti-abortion extremists attack these organizations, they’re attacking the people they provide essential services to everyday. That cannot stand.

DONATE

Your donation supports our media and helps us keep it free of ads and paywalls.