Restoring trust and saving our democracy

This article originally appeared in the Austin American-Statesman. Reprinted with permission.

Václav Havel, the late president of the Czech Republic, wrote that political leaders had a moral responsibility to create “a climate of generosity, tolerance, openness, broadmindedness and a kind of elementary companionship and mutual trust.”

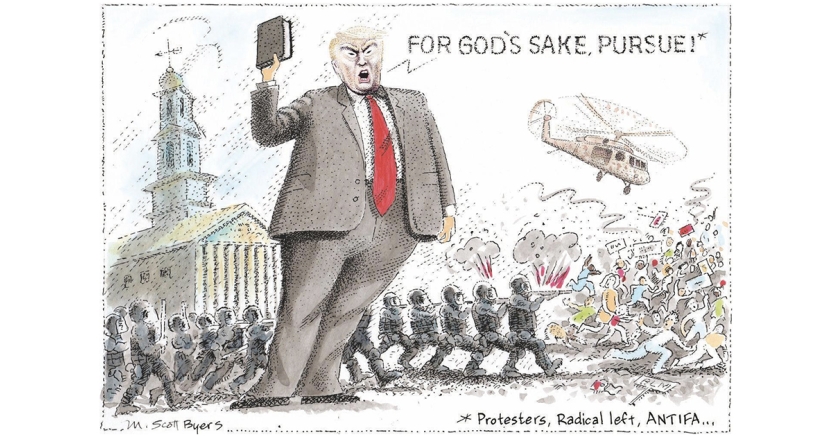

This is the very opposite of President Donald Trump’s agenda. Trump publicly and consciously creates a climate of selfishness, intolerance, secrecy, close-mindedness. He conducts an all-out war on mutual trust among citizens.

The American Right was moving in this authoritarian direction before Trump. He is more a product of the movement than its cause. Too often, of course, some on the Left have taken the bait, responding in ways that reinforce the Right’s view of society as an ongoing war of all against all.

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd and the nationwide protests that followed, many are asking how we might restore trust among citizens and law enforcement. That urgent question needs immediate answers.

The police-citizenry antagonism is part of a larger loss of trust among Americans. A generalized suspicion of others has infected our politics. Without mutual trust, some form of authoritarianism is likely to prevail.

“The most corrupt countries have the least trusting citizens,” wrote political scientist Eric M. Uslaner. “This is hardly surprising, since ‘kleptocracies’ send clear messages to the people that crime does pay. Citizens feel free to flout the legal system, producing firmer crackdowns by authorities and leading to what [Hilary D.] Putnam calls ‘interlocking vicious circles of corruption and mistrust.’”

How, then, do we restore civic trust in a manner that promotes democracy?

The Czech dissidents who brought down their authoritarian government spoke of “living in truth.” They challenged the government to live up its promises to protect human rights in the Helsinki Accords of 1975. The authorities responded with arrests and imprisonments. But the dissidents stuck to their plan and ultimately prevailed.

The movement to end police violence in the U.S. could take a page from Czech dissidents and challenge the nation to live the truth of its commitments. In 1992, the U.S. ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Although the Senate expressed an unprecedented number of objections to other sections, it adopted Article 10.1 without reservation:

“All persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.”

We can break down such a freedom movement into three parts. First, acknowledge the reality of the circumstances and the emotions of fear and suspicion they produce. Second, challenge those circumstances with the truth. Speak the truth, live the truth as a sign of willingness to reconcile and restore trust. Third, give reasons for hope.

That last part should be emphasized. With the loss of trust comes a loss of hope, a formula not lost on authoritarians. To resist, begin a new narrative. If we could hope, what would we hope for? Trust begins in that hope.

DONATE

Your donation supports our media and helps us keep it free of ads and paywalls.