In pipeline politics, love of the land is a shared value

This article originally appeared in the Austin American-Statesman. Reprinted with permission.

We can be fairly certain that gas pipeline giant Kinder Morgan didn’t have this consequence in mind when it decided to route a massive, nearly four-foot diameter gas pipeline through the Texas Hill Country and over the fragile Edwards Aquifer.

That consequence is a renewed understanding among political partisans of all kinds that love of the land is a value shared by all. Well, maybe not the pipeline owners.

The Permian Highway Pipeline cuts through some of what traditional political labeling calls “conservative” counties. But that labeling misses too much of what’s in people’s hearts.

Setting all other differences and antagonisms aside, Texas Hill Country landowners express their love for the land in ways which, say, opponents of the Dakota Access Pipeline so much in the news in 2016 and 2017 would understand and agree with.

The “Permian Highway Pipeline” would transport two billion cubic feet of natural gas per day across the Edwards Aquifer that supplies drinking water to millions of people in Central Texas. It is the sole source of water for San Antonio.

The aquifer is not an underground bowl of water that if contaminated could be rinsed and refilled. It is a “karst” aquifer made of limestone. It’s like a sponge. Poison in one place will show up in another. A pipeline leak south of Kyle could damage Barton Springs in Austin. The Edwards Aquifer can’t be rinsed clean.

There are potential pipeline routes that don’t pose this risk, and it’s curious that Kinder Morgan seems so reluctant to pursue them. This is Texas, and we understand the importance of the oil and gas industry. But why, Kinder Morgan, are you picking such a fight with us when you don’t have to?

Pipeline companies are the only private industry given the right of eminent domain. Eminent, as in “standing above others.” In other words, pipeline companies are more important than you are. If they want your land, they can take it, though they do have to compensate you. Still, you can’t say, “No.”

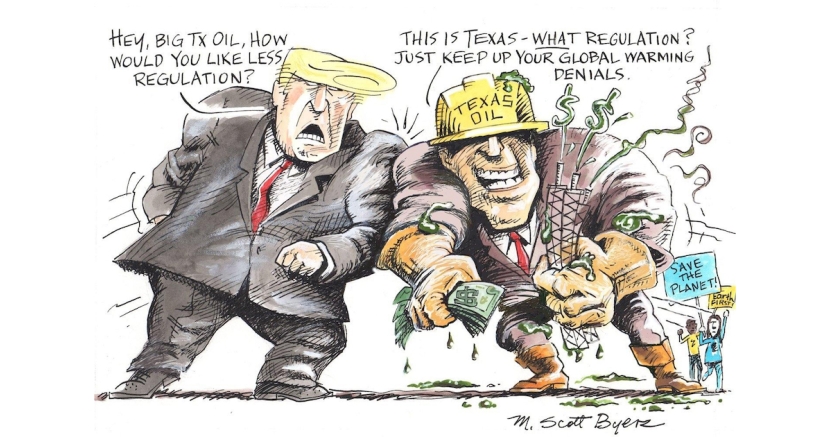

President Donald Trump recently came all the way to Crosby, Texas — where one chemical facility just blew up and another, the very day Trump arrived, found officials under new criminal indictment for an earlier explosion — to plead for less regulation of pipelines.

This is curious since here in Texas we can’t deregulate them because they aren’t really regulated in the first place. It’s harder to get a copy of a birth certificate than to get a pipeline permit.

Maybe Kinder Morgan is just a wee bit carried away by that “eminence” thing. Maybe its management believes any opposition to their wishes is illegitimate in the face of their eminent domain. Maybe in their minds it is no longer just a legal concept. It’s what they believe about their place in the world.

There are several bipartisan efforts underway in the Legislature to reform eminent domain laws and pipeline oversight. Perhaps they will pass. At the very least they have brought our polarized political world together around Texans’ historic love of the land. The effort is a heroic one.

DONATE

Your donation supports our media and helps us keep it free of ads and paywalls.