The divide that matters is between rich and poor

This article originally appeared in the Austin American-Statesman. Reprinted with permission.

The New York Times created some buzz in the Lone Star State recently with a story asserting that Texas’ small towns have been left out of the job growth of the last decade or so. The writer didn’t do his credibility any good when he located Longview on “the eastern plains of Texas,” a description no Texan has ever heard of.

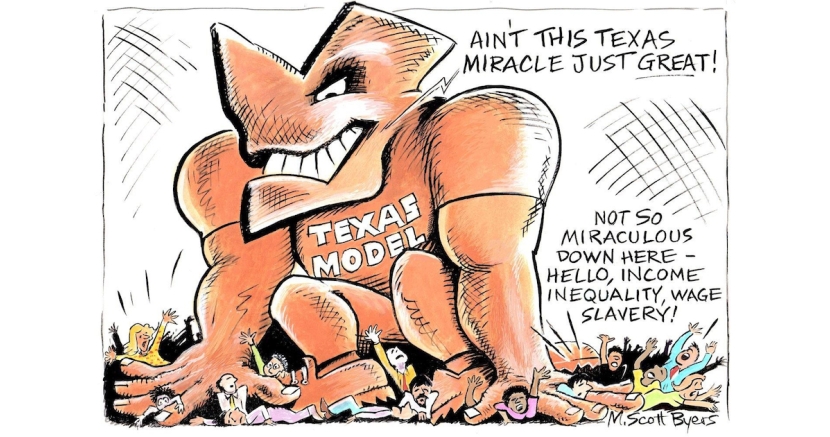

In any case, in both town and city, the so-called “Texas Miracle” is based on wage slavery and alarming spikes in income inequality. It is more catastrophe than miracle.

Texas is an overwhelmingly urban state. Something like 80 percent of us live in one of the six largest metropolitan areas. Urbanization is a global phenomenon, so there’s nothing unique about this trend. The point is, urban-rural contrasts have little meaning anymore. The real story is in the cities, and it’s not pretty.

Take Houston, for example. A new study by Apartment List showed income inequality growing by a whopping 16.3 percent from 2008 to 2017. Top Houston earners make 12.6 times more than lowest wage earners. The bottom 25 percent of households must try to get by on 73 percent less than the median household income, according to the study.

At the same time, domestic migration to our biggest cities has fueled spikes in housing costs. In Houston, housing costs rose 12 percent for households earning less than the national median from 2008-2017; those earning above the median saw a nine percent increase.

Austin appears a bit better, as the study found income inequality actually decreased by 9.5 percent. Appearances, however, can be deceiving − it’s no secret that many are being forced out of Austin neighborhoods by rising housing costs and gentrification. Some of that decrease in income inequality may be due to the poorest folks being forced out of town.

We can acknowledge that any job is better than no job, but we must also acknowledge that Texas has always pursued policies to drive down wages, from anti-union measures to outright wage theft. A recent study found that 11 percent of workers are effectively paid less than the federal minimum wage. About $1 billion a year is stolen from them.

Wage theft happens in many ways. Contractors simply stiff temporary construction workers. Hourly workers in a variety of jobs are forced to work past their shift or are not paid earned overtime. Pay checks bounce. It’s usually the most vulnerable who are victimized, as wage thieves bet workers will be too scared to risk retaliation by reporting the theft.

Let’s leave the world of statistics, though, and take a bird’s eye view. We see a massive wave of people moving to the cities, driving up housing costs and causing a riptide of poor folks to be pulled to the urban periphery.

Making things worse, these folks, whose services are more necessary than ever within the fast-growing urban areas, can barely afford the transportation costs to get from their new homes to their old jobs.

If there is a relevant study to be done with regard to our urban-rural split, it should focus on the lack of adequate transportation options that link urban and suburban Texas to ex-urban and rural Texas.

The current Republican state leadership in Austin seems opposed to high-speed and commuter rail, preferring to build roads that are, in every case, already obsolete by the time they are finished — if they are ever finished. “Miracle” is not the best term to describe this alarming circumstance.

DONATE

Your donation supports our media and helps us keep it free of ads and paywalls.