Bread and roses and Labor Day

This article originally appeared in the Austin American-Statesman. Reprinted with permission.

If the grim expressions on the faces of folks fighting rush hour traffic on the way to their jobs is an indication, we aren’t exactly singing, “Hi ho, hi ho, it’s off to work we go,” during our daily commutes.

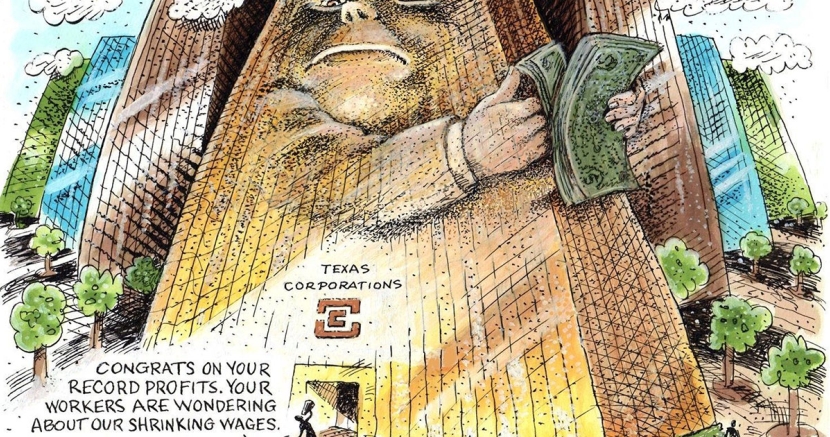

As we celebrate the working people of Texas and America this Labor Day, it’s worth wondering whether years of overwhelming focus on “shareholder value” at the expense of working people is crippling us in ways hard to recover from.

We are working harder and earning less. Income inequality is at levels not seen since the 19th Century. And “job security” is an almost laughable term as employers increasingly turn to temporary services or contract labor.

Recently, even the 181 members of the Business Roundtable, CEOs from the likes of General Electric, Apple and Oracle, recognized the dangers. They issued a statement pledging to provide “a life of meaning and dignity” to workers.

Thematically, that’s not so far off from “bread for all, and roses too,” a slogan and song from the successful 1912 Lawrence, Massachusetts textile workers strike. If American corporate leaders are even close to singing in the same key as leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World of the early 20th Century, you know a new song’s in the air.

We’re suffering through political instability and chaos caused in part by extreme income inequality. Studies indicate that a significant factor in wage stagnation and a shrinking middle class is the decline of organized labor.

The phrase “the decline of organized labor” disguises the fact that it hasn’t declined by some sort of natural process. No, the labor movement was hurt by decades of attacks from corporate bosses who wanted to grow their profits by cutting workers’ wages and benefits.

It hasn’t been all about greed, though. There’s also the “bossy pants” phenomenon. Like authoritarian leaders we decry in the political arena, some bosses are more comfortable with unquestioned authority over others. They are threatened by union members who like to call one another brother and sister, and form lateral lines of loyalty and authority within an organization.

Public opposition to organized labor may be the original “what’s-the-matter-with-Kansas” mystery in American life. All of us, non-union workers, too, do better when unions have negotiated better wages and benefits. That’s an economic fact. Call it trickle-out-and-trickle-up economics. So, why have we so willingly dismissed that fact when it’s our own economic well-being that has declined with the labor movement, whether or not we belong to a union?

Back in the 1940s, states began passing what were called “right to work” laws. An ingenious bit of framing, that. Texas has such a law, and it should be called, “We’ll pay you not a penny more than we want to pay you to work for us, and if you don’t like it you’re fired” law.

Such laws were never about a right to work. They were just another weapon in the corporate arsenal used to keep wages and benefits down. They were designed to weaken and destroy the trade union movement.

Today, unions are fighting back, and we all ought to be glad they are. Happy Labor Day, my brothers and sisters.

DONATE

Your donation supports our media and helps us keep it free of ads and paywalls.