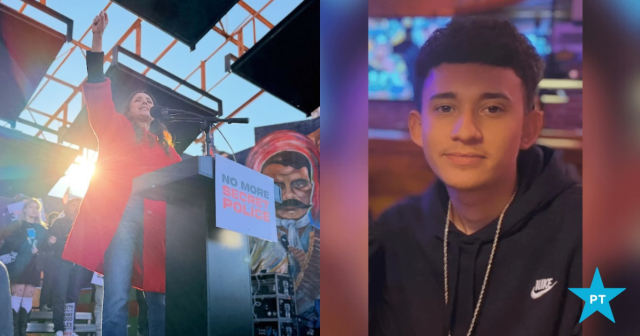

50 Years Ago, César Chávez Led a 490-Mile March for Better Pay to the Texas Capitol

Ed. note: this column originally appeared in the San Antonio Express-News. For more information on the farmworkers movement, go to https://farmworkers2016.org/.

San Antonio will soon join the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of a strike and march by farmworkers engaged in the outdoor sweatshop known as cantaloupe harvesting. The Starr County employers of 1966 were paying farmworkers as little as 40 cents an hour, or about one-third of what sanitation workers of the era made.

On June 1, 1966, Rio Grande City farmworkers launched a strike for better pay. While unions had expressed interest in organizing Texas farmworkers, the strike arrived suddenly. César Chávez, legendary co-founder of the United Farm Workers union, told the Texas AFL-CIO Convention a year later, “Here in the Rio Grande Valley, the strike came about overnight. So we had no experience, no preparation for the strike and we had to take it on immediately.”

That summer, the strike morphed into a 490-mile march, detours to visit towns and cities included, from Rio Grande City to the Texas Capitol. The goal: a state minimum wage law that would apply to farmworkers. The march began on Independence Day and culminated, cinematically, in a cascade of humanity more than 10,000 strong up Congress Avenue.

Moving renditions of “We Shall Overcome” and a dramatic entrance of the farmworker contingent drew tears from crusty activists who thought they had seen it all.

The Capitol rally included Chávez, U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough and U.S. Rep. Henry B. Gonzalez of San Antonio. Hank Brown, the fiery president of the Texas AFL-CIO and a San Antonian, committed the support of the state labor federation, which delivered much of the crowd and passion.

Days earlier, Gov. John Connally met the marchers in New Braunfels and declared he would not “lend the dignity of his office” to a Capitol rally.

Before arriving, the marchers were greeted warmly, usually by church officials, in community after community. In Connally’s hometown of Floresville, the Methodist Church fed them. In Beeville, 1,000 supporters encouraged them. And in San Antonio, Catholic Archbishop Robert E. Lucey, a full-throated supporter of trade unionism, celebrated Mass at San Fernando Cathedral on Aug. 27, 1966, declaring, “Mexican-Americans … must stand up and defend themselves against discrimination and oppression.”

I don’t have room to do justice to the labor rock stars who comprised the farmworker contingent, but let me give you the flavor of these people. Daria Vera, who retains fire in her eyes over the events of 1966, once laid across an international bridge to protest the employment of Mexican strikebreakers. She still joins fellow strikers in singing the corridos (ballads) that those who were arrested for strike activity composed while in jail.

Ismael Diaz recalls stuffing cardboard into his shoes as the soles disintegrated during the march. When the Rev. Ed Krueger describes his exploits in Spanish, he breaks into English to quote precisely the Texas Ranger who informed him, “Krueger, you’re not a preacher. You’re just a troublemaker.”

Alex Moreno, who went on to become a respected state representative, quietly discusses the time he was beaten inside a striker’s home as Rangers sought another striker.

Some are no longer with us. Magdaleno Dimas suffered a beating that curved his spine out of shape and caused a concussion. He died young. The corrido “Los Rinches de Tejas” references the deadly beating and is an enduring example of how the art form empowers people to tell an alternative kind of history.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, the weapon of choice in putting down strikes had been Pinkerton detective agency operatives. In the 1960s, Texas, as always, wanted to do this on the cheap. The busting of the farmworkers’ strike was carried out by government officials, in the form of the Rangers and even Starr County deputy sheriffs who dutifully became paperboys, passing out anti-union newspapers.

No, I’m not making this up. The U.S. Supreme Court reported in the case of Allee vs. Medrano that Texas law officers were engaged in even more interesting activities:

• Raymond Chandler, a union leader, got stuck with a $500 bond for a misdemeanor arrest when the maximum penalty he faced was a $200 fine. When friends arrived to bail out Chandler, they were threatened with arrest and told to leave.

• When arrested strikers shouted “Viva la huelga” (“Long live the strike”), a deputy sheriff struck the local union president and held a gun to his forehead.

• Texas Rangers held the faces of Krueger and Dimas within inches of a moving train after taking them into custody.

Amid government intimidation, the strikers lost the short-term fight, big-time. They did not get a raise or a special legislative session. The strike withered away in 1967, not long after the Dimas beating.

The long run is different. Farmworkers eventually won a minimum wage and other protections in Texas, with lawmakers such as Sen. Joe Bernal, D-San Antonio, leading the way. The Supreme Court decision in Medrano vs. Allee effectively ended the use of taxpayer-funded law officers to wage war against labor unions. The anti-picketing laws became a dead letter, cementing First Amendment rights for all of us.

Another huge change: Latinos began exercising their power to choose elected officials under the Voting Rights Act. At the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the strike in Rio Grande City, the mayor and county judge, along with sheriff’s deputies, joined enthusiastically in the celebration of the huelgistas.

Rebecca Flores, the former UFW leader in Texas who is coordinating the golden anniversary events, notes she has drawn no contradiction in asserting the strike launched the Chicano Movement in Texas. However one writes the categories, the strikers and marchers laid groundwork for Henry Cisneros, the Castro brothers and other outstanding Mexican-American politicians. Ernesto Cortes, the brilliant moving force behind the Industrial Areas Foundation, launched his community advocacy after putting his academic life on hold to work with the farmworkers.

Here’s a thought: Knowing the story of the 1966 strike and march gives us perspective as history repeats. In 2016, the fight for living wages is as pitched as ever. In 2016, farmworker housing remains atrocious in some quarters, with little enforcement of the law. In 2016, Latinos do not exploit their full potential strength at the polls. But in 2016, it is still possible for ordinary people to do extraordinary things. As the strikers and marchers of 1966 showed, when you get knocked down, get back up, rinse and repeat, and magic can happen.

Want to meet some unassuming people whose courage made a difference? The San Antonio commemoration of the 1966 farmworker strike and march will start at 10 a.m. Sept. 5, with Mass at San Fernando Cathedral, followed by a march and a rally at Milam Park.

Ed Sills is director of communications at the Texas AFL-CIO, a state labor federation whose 237,000 affiliated members advocate for a raising-wages agenda in Texas.

DONATE

Your donation supports our media and helps us keep it free of ads and paywalls.